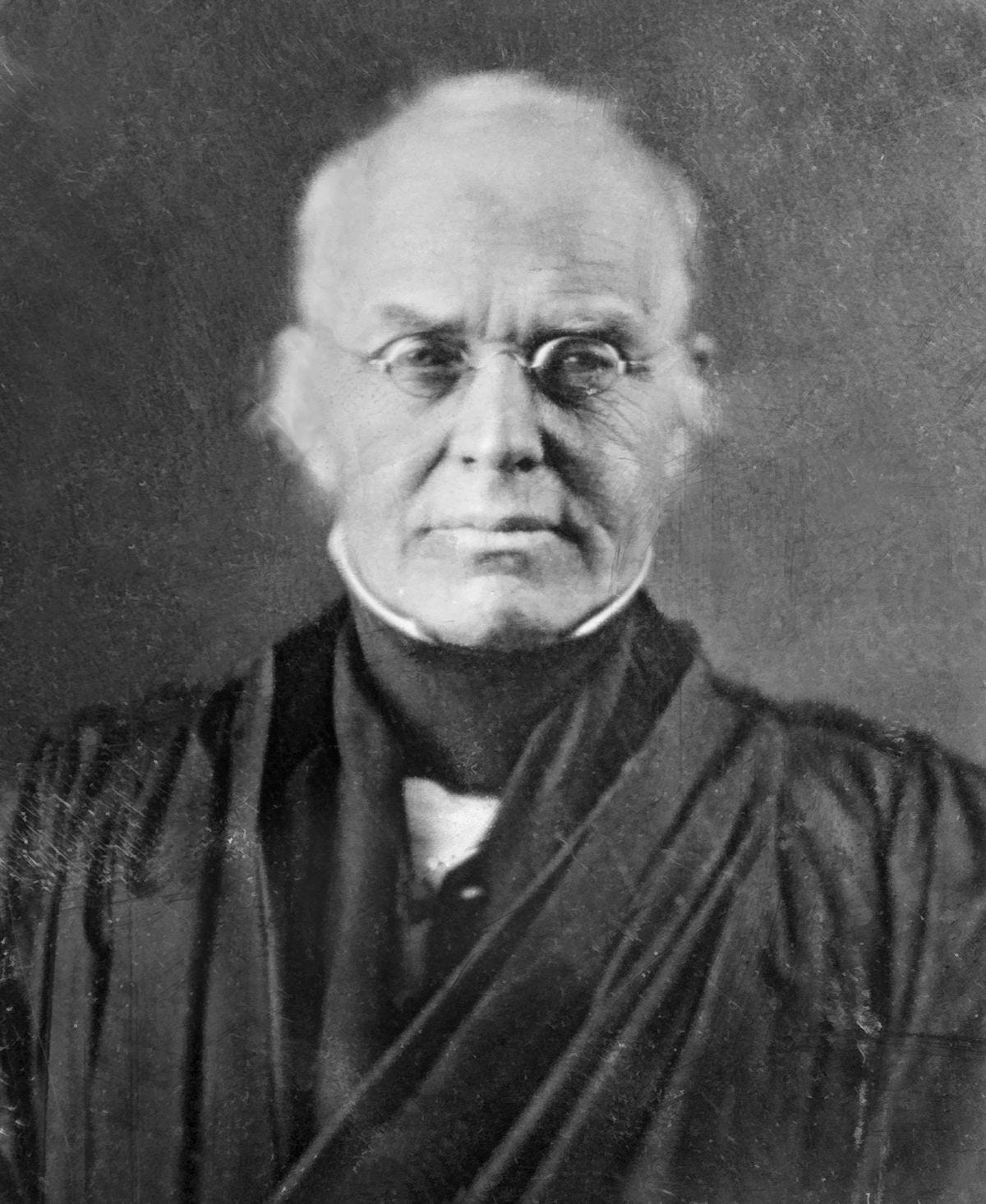

Supreme Court Justice Joseph L. Story (1779-1845) is one of the most important figures in American constitutional history. He served on the high court for 33 years (1812-1845), under both Chief Justice Marshall, whom he deeply admired, and Justice Taney, author of the infamous Dred Scott decision, and with whom he had a troubled relationship.

Story authored the famous Amistad decision, which came after a long contentious international dispute regarding the disposition of a Spanish slave ship and the captives on board, and about which the 1997 film Amistad was made. In the end, Story ruled that the captives, who were not slaves at the time of their abduction, could not be sold into slavery and were indeed free. The ship captains were ultimately arrested and charged with illegal slave-trading.

In addition to his tenure on the U.S. Supreme Court, Story was a prolific writer on the American founding, the U.S. Constitution, and law. He released a grand treatise, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States, in 1833. The purpose for the treatise, according to Story himself, was “to present a full analysis and exposition of the Constitution of Government of the United States of America.”

Story described the project more fully this way.

In order to do this [explain the Constitution] with clearness and accuracy, it is necessary to understand what was the political position of the several States, composing the Union, in relation to each other at the time of its adoption. This will naturally conduct us back to the American Revolution; and to the formation of the Confederation consequent thereon.

But if we stop here, we shall still be surrounded with many difficulties in regard to our domestic institutions and policy, which have grown out of transactions of a much earlier date, connected on one side with the common dependence of all the Colonies upon the British Empire, and on the other with the particular charters of government and internal legislation, which belonged to each Colony, as a distinct sovereignty, and which have impressed upon each peculiar habits, opinions, attachments, and even prejudices.

… In short, without a careful review of the origin and constitutional and juridical history of all the colonies, of principles common to all, and of the diversities, which were no less remarkable in all, it would be impossible fully to understand the nature and objects of the Constitution; the reasons on which several of its most important provisions are founded; and the necessity of those concessions and compromises, which a desire to form a solid and perpetual Union has incorporated into its leading features.

I agree with Story 100% and regret that I was never introduced to him, or these commentaries, while in law school - or ever while actively practicing law. Indeed, no law student since the late 19th century as been introduced to him - save those who are lucky enough to take a course not just in the technical aspects of constitutional law, but in constitutionalism, the philosophical underpinnings of the Constitution - or have a conservative law professor discuss it off hand.

Law students are simply taught how case law has unfolded and how to deploy precedents with doctrine (which is positive, or manmade, law), but are not exposed to the role of the natural-law tradition (which transcendental, or revealed, law combined with human reasoning) in the evolution of the Anglo-American legal world.

This omission is a huge flaw in American legal education and, I believe, has contributed widely to the vacuous nature of my profession.

Back to Justice Story …

Story’s Commentaries are organized in three (3) parts. He describes them as follows (his words, not mine):

Part One (aka Volume 1)

Review of the colonial charters of government and internal legislation

Constitutional history

Ante-revolutionary jurisprudence (law before the revolution) in the Colonies

Part Two (aka Volume 2)

Sketch the constitutional history of the States during the Revolution, and

the rise, progress, decline, and fall of the Confederation

Part Three (aka Volume 3)

Explore the history of the rise and adoption of the Constitution

A full exposition of all its provisions … with the reasons, on which they were respectfully founded, the objections, by which they were respectively assailed, and

such illustrations drawn from contemporaneous documents, and the subsequent operations of the government, as may best enable the reader to estimate for himself the true value of each.

Story hoped that by organizing the commentaries this way, the reader’s “judgment as well as his affections will be enlisted on the side of the Constitution, as the truest security of the Union, and the only solid basis, on which to rest the private rights, the public liberties, and the substantial prosperity of the people composing the American Republic.”

As a reader, I have - after an enormous amount of study and reflection - situated myself on the side of the Constitution.

This position is under bombardment today, particularly through Critical Race Theory (CRT), which holds that the U.S Constitution is incapable of securing the rights of blacks to the same extent it does for whites. CRT is an outgrowth of critical legal studies, a movement that criticizes and rejects liberalism, the political and social philosophy that promotes individual rights, civil liberties, democracy and free enterprise (which Karl Marx coined as capitalism), in favor of Marxism, the political and social philosophy that promotes collectivism and redistribution of wealth (material and privilege) through state action. This stands in direct contrast to classical liberalism (not liberalism in context of liberal v. conservative) and has huge implications for understanding, interpreting, and establishing the purpose of law in a society.

You may know that Marxism claims the state has been the means of “exploitation of the masses [the oppressed] by a dominant class [the oppressors] and that “the capitalist system … after a period of the dictatorship of the proletariat [the oppressed masses]” attained by overtaking the bourgeoise [the owners of capital and therefore oppressors] … will [inevitably be superseded by a socialist order.” One of the key tools Marxists use to implement their ideology is reimagining and reinterpreting the law and then leveraging it as a tool of social change, starting with Declaration and the U.S. Constitution.

This is why I am utterly confused by the idea of a woke lawyer. Woke is Marxist, but lawyers take an Oath to defend the Constitution, not to destroy it.

But, no one asked me what I think … and I digress … :-)

—

In this “Founding of America” section of The Savvy Citizen, we will use Justice Story’s Commentaries as our guide. Fortunately, his work is in the public domain, so we can all access it for free.

Here are a few options:

You can download a modern version of Commentaries from the LONANG Institute. Just click on the image below (it’s the cover image of the LONANG repro).

Or you can access copies of the original texts by hovering over and clicking on the three instances of the word VOLUME below. It’s always fun to see things as originally presented, at least to me anyway!

Book 1: History of the Colonies

Chapter 1: Origin and Title to the Territory of the Colonies

Chapter 2: Origin and Settlement of Virginia

Chapter 3: Origin and Settlement of New-England, and Plymouth Colony

Chapter 4: Massachusetts

Chapter 5: New-Hampshire

Chapter 6: Maine

Chapter 7: Connecticut

Chapter 8: Rhode-Island

Chapter 9: Maryland

Chapter 10: New-York

Chapter 11: New-Jersey

Chapter 12: Pennsylvania

Chapter 13: Delaware

Chapter 14: North and South-Carolina

Chapter 15: Georgia

Chapter 16: General Review of the Colonies

Book 2: History of the Revolution and of the Confederation

Chapter 1: The History of the Revolution

Chapter 2: Origin of the Confederation

Chapter 3: Analysis of the Articles of the Confederation

Chapter 4: Decline and Fall of the Confederation

Book 3: The Constitution of the United States

Chapter 1: Origin and Adoption of the Constitution

Chapter 2: Objections to the Constitution

Chapter 3: Nature of the Constitution - Whether a Compact

Chapter 4: Who is the final Judge or Interpreter in Constitutional Controversies

Chapter 5: Rules of Interpretation of the Constitution

Chapter 6: The Preamble

VOLUME 2 (the Chapter titles pick up where Part 1 / Book 3 left off)

Chapter 7: Distribution of Powers

Chapter 8: The Legislature

Chapter 9: The House of Representatives

Chapter 10: The Senate

Chapter 11: Elections and Meeting of Congress

Chapter 12: Privileges and Powers of both Houses of Congress

Chapter 13: Mode of Passing Laws - President’s Negative

Chapter 14: Powers of Congress - Taxes

Chapter 15: Power to Borrow Money and Regulate Commerce

Chapter 16: Power over Naturalization and Bankruptcy

Chapter 17: Power to Coin Money and Fix the Standard of Weights and Measures

Chapter 18: Power to Establish Post-Offices and Post-Roads

Chapter 19: Power to Promote Science and the Useful Arts

Chapter 20: Power to Punish Piracies and Felonies on the High Seas

Chapter 21: Power to Declare War and Make Captures - Army / Navy

Chapter 22: Power Over the Militia

Chapter 23: Power Over Seat of Government and Other Ceded Places

Chapter 24: Powers of Congress - Incidental

Chapter 25: Powers of Congress - National Bank

Chapter 26: Powers of Congress - Internal Improvements

Chapter 27: Powers of Con Congress - Purchase of Foreign Territory - Embargoes

Chapter 28: Powers of Congress to Punish Treason

Chapter 29: Power of Congress as to Proof of State Records and Proceedings

Chapter 30: Powers of Congress - Admission of new States, and Acquisition of Territory

Chapter 31: Powers of Congress - Territorial Government

Chapter 32: Prohibitions on the United States

Chapter 33: Prohibitions on the States

Chapter 34: Prohibitions on the States - Impairing Contracts

Chapter 35: Prohibition of the States - Tonnage Duties - Making War

Chapter 36: Executive Department - Organization of

Chapter 37: Executive - Powers and Duties

Chapter 38: The Judiciary - Importance and Powers of

Chapter 39: Definition and Evidence of Treason

Chapter 40: Privileges of Citizens - Fugitives - Slaves

Chapter 41: Guaranty of Republican Government - Mode of Making Amendments

Chapter 42: Public Debts - Supremacy of the Constitution and Laws

Chapter 43: Oaths of Office - Religious Test - Ratification of the Constitution

Chapter 44: Amendments to the Constitution

Chapter 45: Concluding Remarks

Story also published two abridged versions of his book:

The Constitutional Class Book: Being a Brief Exposition of the Constitution of the United States (1834) - which was designed for the use of the “higher classes in common schools.” Essentially, this was primary school civics book.

A Familiar Exposition of the Constitution of the United States: A Brief Commentary (1940) - which serves an advanced version of the Class Book for those in what we now call honors programs, college students, and, per the preface, for those “who have arrived at maturer years, but whose pursuits have not allowed them leisure to acquire a thorough knowledge of the Republican Constitution of Government, under which they live.”

We will be using all three as reference points while working through the material.

—

Why All of this Effort?

In an article in National Affairs entitled Two Kinds of Originalism, author Steven F. Hayward closes his piece with the following text:

One of the defects of our age is the tendency, frequently reinforced by the Supreme Court and the legal guild, to regard the Constitution as the near-exclusive property of lawyers rather than the general property of all American citizens, as the preamble should remind us.

Citizens should contest for the meaning of the Constitution just as much as lawyers do. Constitutional government cannot be restored by legal action alone. It requires us to follow the model of great teachers and thinkers and to ask ourselves hard questions about the roots of law and justice.

We’re undertaking this project because the U.S. Constitution should not be the near-exclusive property of lawyers, but because it is the general property of all American citizens, as clarified in the Preamble to the Constitution.

It’s We, the People, not We, the Lawyers.

We the People of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

There’s a lot to cover and a lot to do … and we will do so thoughtfully, methodically, and steadfastly.

Buckle up, we’re going back to the beginning … of America.

xo,

The Savvy Citizen Team

P.S. Once we introduce each section of The Savvy Citizen, I’ll have a better sense for the pace we’ll take through the founding.

The essence of the study of history and historical texts involves the review of original sources -- but importantly -- such review should be done with a thorough understanding of the context in which it was written. As you alluded with CRT and critical theory generally, one of the many flaws of those destructive ideas is that they attempt to impose subjective modern sensibilities onto the historical text, which leads to flawed analysis and conclusions and dangerous propositions for future steps.

I applaud your dive into Story, who was an impressive intellect.